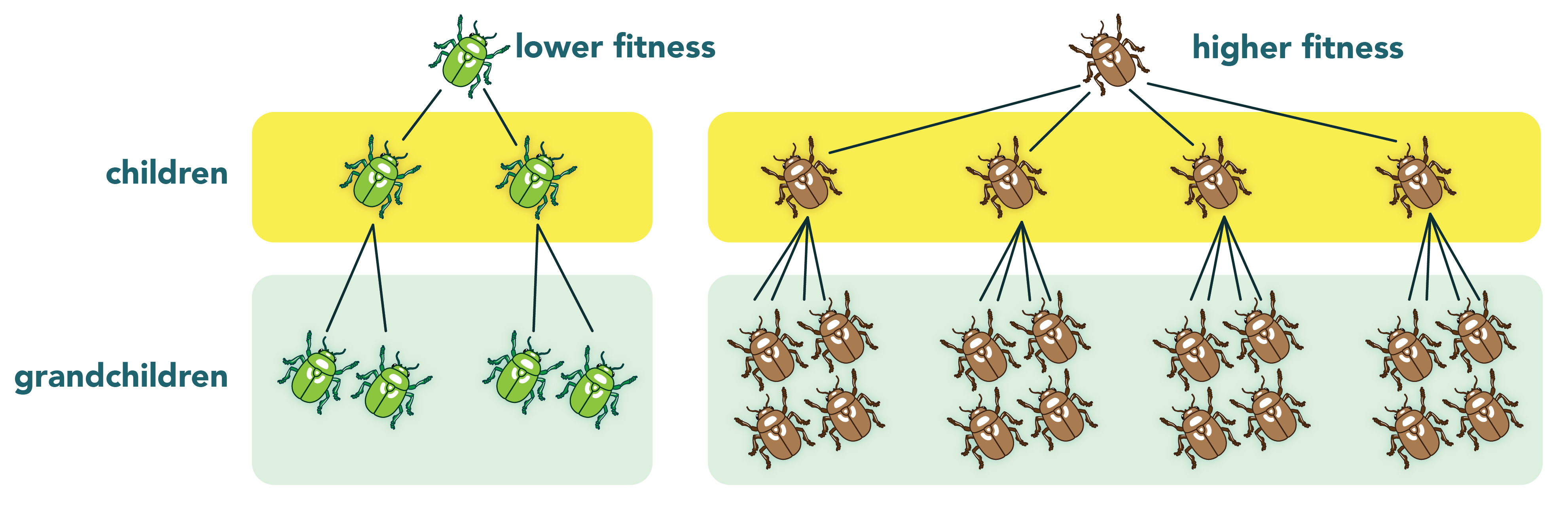

What is evolutionary fitness? Evolutionary fitness is a measure of an organism’s ability to survive and reproduce in its environment. How is it measured? It’s measured by looking at how many offspring an organism has that can also reproduce, and how well those offspring survive.

In the grand theater of life, every organism plays a role, and its success is judged not by its perceived beauty or strength, but by its ability to pass on its legacy. This passing of a legacy is what evolutionary biologists call “fitness.” But what exactly does fitness mean in an evolutionary context? It’s not about how many muscles you have or how fast you can run. Instead, it’s a much deeper, more fundamental measure of how well an organism is suited to its environment and how effectively it contributes to the next generation.

Image Source: evolution.berkeley.edu

Deciphering Evolutionary Fitness: The Core Concepts

At its heart, evolutionary fitness is about reproductive success. An organism that is highly “fit” is one that leaves behind a greater number of viable offspring compared to others in its population. This isn’t just about having a lot of babies; it’s about those babies growing up, surviving, and then themselves being able to reproduce. Think of it as a generational relay race, where passing the baton (genes) successfully is the ultimate goal.

This concept is intrinsically linked to natural selection. Nature, in its infinite wisdom and sometimes harsh reality, acts as a filter. Organisms with traits that make them better suited to their environment are more likely to survive and reproduce. These advantageous traits are then passed down, leading to populations that become increasingly adapted over time. Fitness, therefore, is the currency of natural selection.

Survival Rate: The First Hurdle

Before an organism can even think about reproduction, it must first survive. A higher survival rate is a crucial component of fitness. If an organism is eaten by a predator, succumbs to disease, or can’t find enough food, its reproductive potential is immediately cut short. Traits that enhance survival, such as camouflage, resistance to disease, or efficient foraging, contribute directly to an organism’s fitness.

Imagine a population of rabbits in a field. Some have fur that blends in with the grass, while others have brightly colored fur. The camouflaged rabbits are less likely to be spotted by foxes. This means they have a higher survival rate. Because they survive longer, they have more opportunities to mate and produce offspring.

Offspring Count: The Direct Measure

The most direct way to assess evolutionary fitness is by looking at the offspring count. An individual that produces more offspring that survive to reproduce is considered more fit. This is a simple yet powerful metric. However, it’s not just about quantity; it’s also about quality. A large number of offspring that quickly die off before reaching reproductive age does not contribute much to the long-term genetic success of a lineage.

Consider a bird species. One bird might lay 10 eggs, but only 2 of those chicks survive to fledging and then to adulthood. Another bird might lay only 4 eggs, but all 4 chicks survive and eventually reproduce themselves. In this scenario, the second bird, despite laying fewer eggs, might have higher overall fitness because a larger proportion of its offspring contribute to the next generation.

Genetic Contribution: The Ultimate Goal

Ultimately, evolutionary fitness is about genetic contribution. Every offspring an organism produces carries a portion of its genes. The more offspring an organism has that reach reproductive age and reproduce, the greater its genetic contribution to the future gene pool of the population. This is the grand prize in the evolutionary game.

Traits that are heritable – meaning they can be passed down from parent to offspring – are what natural selection acts upon. If a trait increases an organism’s chances of survival and reproduction, it will become more common in the population over generations. This gradual change in the genetic makeup of a population is evolution itself.

Factors Influencing Evolutionary Fitness

Several factors can influence an organism’s evolutionary fitness. These often interact in complex ways, creating a dynamic and ever-changing landscape.

Adaptation: Fitting into the Environment

Adaptation is the process by which organisms evolve traits that make them better suited to their environment. These adaptations can be structural, physiological, or behavioral. For example, a cactus has adapted to desert life with its waxy coating to prevent water loss and spines to deter herbivores. These adaptations directly increase its chances of survival and reproduction in a harsh environment, thus boosting its fitness.

The Fitness Landscape: A Conceptual Map

The concept of a fitness landscape helps visualize how different combinations of traits affect an organism’s fitness. Imagine a topographical map where the height represents fitness, and the position on the map represents a combination of traits. Peaks on the landscape represent combinations of traits that lead to high fitness, while valleys represent combinations that lead to low fitness.

Natural selection can be thought of as an organism “climbing” this landscape, moving towards higher fitness by acquiring advantageous traits. However, the landscape isn’t static. Environmental changes can alter the fitness landscape, making previously beneficial traits less useful or even detrimental, and vice versa.

Fitness Coefficient: Quantifying the Advantage

In some mathematical models of evolution, a fitness coefficient is used to quantify the relative fitness of different genotypes. For example, if one genotype has a fitness of 1.0 (considered the baseline), a genotype with a fitness coefficient of 1.2 would be considered 20% more fit, meaning it would produce more offspring on average. Conversely, a fitness coefficient of 0.8 would indicate 20% less fitness.

This allows for a more precise way to study how natural selection might favor certain genetic variations within a population.

Heritability: Passing on the Advantages

For a trait to be subject to natural selection and influence evolutionary fitness, it must be heritable. Heritability refers to the proportion of variation in a trait that is due to genetic differences among individuals. If a trait is highly heritable, then offspring are likely to resemble their parents in that trait.

Consider wing length in birds. If wing length is highly heritable, and longer wings provide a survival advantage (e.g., for migration), then individuals with longer wings will likely have more offspring, and those offspring will also tend to have longer wings. Over time, the average wing length in the population will increase.

Measuring Fitness in Practice: Methods and Challenges

Measuring evolutionary fitness directly in the wild can be challenging. Biologists often use a variety of methods to estimate it.

Direct Observation and Counting

The most straightforward method is to directly observe a population over time, count the number of offspring each individual produces, and track their survival to reproductive age. This is often feasible for organisms with short generation times and easily observable life cycles, like bacteria or fruit flies.

Table 1: Example of Direct Fitness Measurement (Hypothetical)

| Individual ID | Number of Offspring Produced | Number of Offspring Surviving to Reproduce | Relative Fitness (Offspring Surviving) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alice | 15 | 8 | 1.00 |

| Bob | 12 | 6 | 0.75 |

| Carol | 20 | 10 | 1.25 |

| David | 10 | 5 | 0.63 |

In this simplified example, Carol has the highest relative fitness because she has the most offspring that survive to reproduce.

Indirect Measures: Proxies for Reproductive Success

Often, direct measurement is not practical. In such cases, biologists use indirect measures, or proxies, that are correlated with reproductive success. These can include:

- Survival Rate: As discussed, surviving to reproduce is paramount.

- Mating Success: The number of mates an individual secures can be a good indicator, especially in species with complex mating rituals or competition.

- Fecundity: The total number of eggs produced or young born.

- Growth Rate: For some organisms, faster growth can lead to earlier reproduction.

- Nutritional Status: A healthier, well-nourished individual may have more resources to invest in reproduction.

These proxies can provide valuable insights, but it’s important to remember they are not direct measures of fitness and can sometimes be misleading if the correlation with actual reproductive success is weak.

Laboratory Experiments

Controlled laboratory experiments are invaluable for precisely measuring fitness. Researchers can manipulate environmental conditions, introduce specific genetic variations, and meticulously track survival and reproduction rates. This allows for the isolation of the effects of particular traits on fitness.

For instance, a scientist might study the fitness of two strains of bacteria, one with a gene conferring antibiotic resistance and one without. By exposing both strains to an antibiotic and measuring their growth and reproduction, they can determine the fitness advantage conferred by the resistance gene.

Genetic Data and Modeling

With advances in genomics, researchers can also infer fitness based on genetic data. By analyzing the frequency of different genes or alleles within a population over time, they can observe which ones are becoming more or less common. An allele that consistently increases in frequency is likely associated with higher fitness.

Mathematical models are then used to predict how these genetic changes will affect the population’s overall fitness and evolution. These models can incorporate various factors like differential reproduction – the idea that different individuals within a population have different rates of reproduction.

Challenges in Measuring Evolutionary Fitness

While the concept of fitness is central to evolutionary theory, its practical measurement is fraught with complexities.

Environmental Variation

The environment is rarely stable. Changes in temperature, availability of food, presence of predators, or introduction of diseases can all alter the fitness of individuals. What makes an organism fit today might not make it fit tomorrow. This dynamic nature makes long-term fitness tracking difficult.

Competition and Social Factors

Fitness isn’t solely determined by an organism’s intrinsic qualities; it’s also influenced by its interactions with others in the population. Competition for resources, cooperation, and social hierarchies can all play a role. An individual might be well-adapted to its environment but struggle to reproduce if it’s outcompeted by others for mates or food.

Trade-offs

Evolutionary adaptations often involve trade-offs. For example, a brightly colored plumage might attract mates (increasing reproductive success) but also make the bird more visible to predators (decreasing survival rate). The net effect on fitness depends on the specific environment and the balance of these competing pressures.

Measuring “Fitness” Itself

The very act of measuring fitness can sometimes influence it. For example, tagging an animal for tracking might make it more vulnerable to predation. Researchers must be mindful of how their methods might impact the very thing they are trying to measure.

The Importance of Relative Fitness

It’s crucial to remember that fitness is almost always measured relatively. An organism isn’t absolutely fit or unfit; its fitness is judged in comparison to other individuals within its population. The “fittest” individual is simply the one that leaves the most successful offspring in that specific context.

This is why a trait that confers high fitness in one environment might be neutral or even detrimental in another. The adaptation that makes a desert plant thrive in arid conditions would be disastrous in a lush rainforest.

FAQs About Evolutionary Fitness

Q1: Is evolutionary fitness the same as physical fitness?

No. Physical fitness refers to an organism’s physical condition, like strength and endurance. Evolutionary fitness is about reproductive success and the passing of genes to the next generation.

Q2: Can an organism have zero evolutionary fitness?

Yes. An organism that dies before reproducing, or reproduces but its offspring do not survive to reproduce, has zero evolutionary fitness.

Q3: Does evolution favor only the “strongest” or “fastest”?

Not necessarily. Evolution favors whatever traits are most advantageous for survival and reproduction in a given environment. This could be being strong or fast, but it could also be being small, camouflaged, efficient at conserving energy, or even being able to form strong social bonds.

Q4: How do scientists estimate evolutionary fitness for extinct species?

Estimating fitness for extinct species is very difficult and relies heavily on fossil evidence and comparative anatomy. Scientists infer potential advantages or disadvantages based on inferred lifestyle, diet, and environmental conditions. It’s an indirect and often speculative process.

Q5: Does successful reproduction always mean high evolutionary fitness?

Not entirely. While reproduction is the primary driver, the survival of the offspring to reproductive age is also critical. An organism that has many offspring but none survive to reproduce has low evolutionary fitness.

In conclusion, evolutionary fitness is a multifaceted concept, a dynamic measure of an organism’s ability to contribute to the perpetuation of its lineage. It is the engine of natural selection, driving the incredible diversity and adaptability of life on Earth. By examining survival rates, offspring counts, and genetic contributions, scientists strive to decipher the intricate strategies organisms employ to succeed in the ongoing evolutionary journey.