Can exercise cause blood clots? Generally, no. For most healthy individuals, exercise is a powerful tool to prevent blood clots. However, there are specific circumstances where intense or prolonged exercise, coupled with underlying risk factors, might contribute to the formation of blood clots. This article delves into the relationship between exercise and blood clots, explaining how it can be both a preventative measure and, in rare cases, a contributing factor.

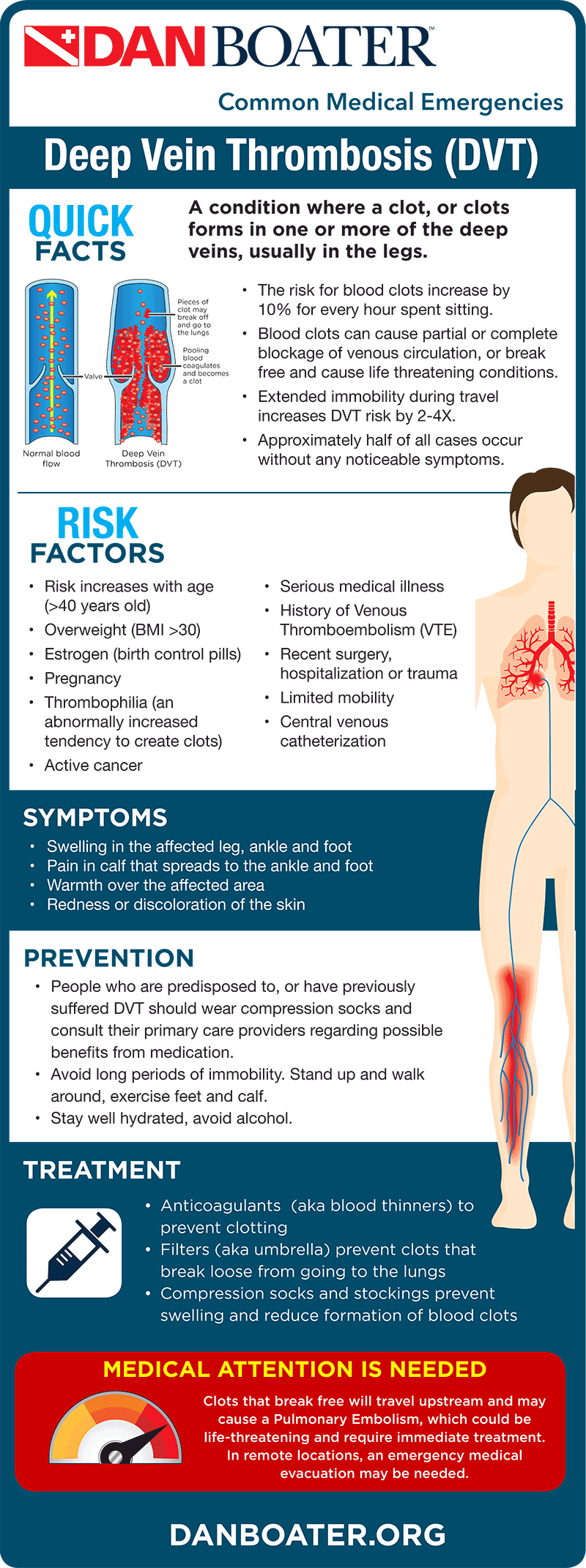

Image Source: danboater.org

Deciphering the Link: Exercise and Blood Clots

The idea that exercise might lead to blood clots can be unsettling, especially given its widely recognized health benefits. It’s crucial to differentiate between the typical effects of exercise on the body and the specific conditions that could elevate clot risk.

How Exercise Typically Benefits Circulation

Exercise is fantastic for your circulatory system. It strengthens your heart, improves blood flow, and helps keep your blood vessels healthy. Here’s a breakdown of its positive impacts:

- Improved Blood Flow: When you exercise, your muscles work harder, requiring more oxygen and nutrients. This increased demand stimulates your heart to pump more blood. Your blood vessels also dilate (widen), allowing blood to move more freely.

- Reduced Blood Stasis: A sedentary lifestyle is a major risk factor for blood clots. Prolonged sitting or standing can cause blood to pool in the legs, a condition known as venous stasis. Exercise, especially activities that involve leg movement, actively combats this by pushing blood back towards the heart.

- Healthier Blood Vessels: Regular physical activity helps maintain the elasticity and health of your blood vessel walls. This reduces the likelihood of damage or inflammation that could trigger clot formation.

- Weight Management: Obesity is another significant risk factor for blood clots. Exercise plays a vital role in weight management, indirectly reducing clot risk.

- Better Blood Coagulation Control: While exercise doesn’t directly control blood coagulation (the process of blood clotting), it contributes to overall cardiovascular health, which indirectly supports a more balanced clotting system.

When Exercise Might Pose a Risk: The Nuances

While exercise is overwhelmingly beneficial, certain situations can tip the scales, potentially increasing the risk of blood clots, particularly Deep Vein Thrombosis (DVT).

1. Intense Exercise and Dehydration

Pushing your body to its absolute limits without proper preparation and recovery can sometimes lead to complications.

- Dehydration Exercise Blood Clots: When you exercise intensely, you lose fluids through sweat. If this fluid loss isn’t adequately replenished, you can become dehydrated. Dehydration thickens your blood, making it more prone to clotting. Think of it like concentrating juice – the components become more packed together.

- Blood Coagulation Exercise: In a dehydrated state, the blood’s viscosity increases. This means it’s thicker and flows less easily, potentially promoting blood coagulation and increasing DVT risk exercise.

- Intense Exercise Blood Clots: Extremely prolonged or high-intensity exercise, especially in hot conditions, significantly elevates the risk of dehydration. If not managed, this can contribute to a pro-thrombotic (clot-forming) state.

2. Prolonged Immobility After Intense Exercise

Paradoxically, the period immediately following very strenuous activity can also be a concern if you remain immobile.

- Venous Stasis Exercise: After a grueling workout, especially if you’re fatigued, you might sit or lie down for an extended period. If this immobility follows intense exercise, especially if there’s underlying inflammation or dehydration, it can contribute to venous stasis exercise, where blood flow slows down, particularly in the legs. This slow flow is a classic precursor to clot formation.

- Sedentary Lifestyle Blood Clots: While this isn’t directly caused by exercise, the inactivity after exercise can mirror the risks associated with a generally sedentary lifestyle blood clots.

3. Underlying Health Conditions

For individuals with pre-existing conditions, exercise can interact with these risks.

- Blood Clots Exercise: People who have a history of blood clots, clotting disorders, or conditions that affect blood flow (like certain autoimmune diseases or cancers) may be more susceptible.

- Pulmonary Embolism Exercise: A pulmonary embolism (PE) occurs when a blood clot travels to the lungs. While exercise itself doesn’t cause a PE, a DVT that forms due to underlying risks (potentially exacerbated by extreme dehydration or immobility after intense exercise) could dislodge and travel to the lungs. This is a serious, life-threatening condition.

- Exercise Induced Thrombosis: This term refers to the formation of blood clots triggered by exercise. It’s exceptionally rare and usually occurs in individuals with significant underlying risk factors for thrombosis, such as genetic clotting disorders or severe dehydration during extreme endurance events.

4. Overtraining and Inflammation

Overtraining can lead to systemic inflammation, which can indirectly affect the blood’s tendency to clot.

- Exercise Muscle Cramps Blood Clots: While muscle cramps themselves are not direct causes of blood clots, they can be a symptom of electrolyte imbalances or dehydration, which can contribute to thicker blood. In very rare instances, severe muscle damage (rhabdomyolysis) from extreme overexertion can release substances into the bloodstream that potentially increase clot risk, but this is highly uncommon.

Recognizing the Risk Factors

It’s essential to acknowledge that the risk of exercise-related blood clots is not uniform. Several factors can increase an individual’s susceptibility:

Individual Risk Factors

- History of Blood Clots: If you’ve had a DVT or PE before, your risk is higher.

- Clotting Disorders: Genetic conditions like Factor V Leiden or protein C/S deficiencies significantly increase clotting risk.

- Certain Medical Conditions: Cancer, inflammatory bowel disease, autoimmune diseases (like lupus), and heart failure can all increase clot risk.

- Surgery or Injury: Recent surgery or significant injury can put you at higher risk for a period.

- Prolonged Immobility: Long flights, car rides, or bed rest increase the risk of venous stasis.

- Hormonal Factors: Oral contraceptives, hormone replacement therapy, and pregnancy are known to increase clotting risk.

- Smoking: Smoking damages blood vessels and thickens blood, increasing overall clot risk.

- Obesity: Excess weight is a significant risk factor for DVT and PE.

- Age: The risk of blood clots generally increases with age.

Exercise-Specific Risk Amplifiers

- Extreme Endurance Events: Marathons, ultra-marathons, and triathlons, especially in hot weather, pose a risk due to prolonged exertion and potential for dehydration if fluid intake isn’t managed meticulously.

- Inadequate Hydration: Not drinking enough fluids before, during, and after exercise is a primary culprit.

- Insufficient Recovery: Jumping into another intense session without allowing the body to recover can exacerbate potential issues.

- Sudden Increase in Intensity/Duration: Significantly ramping up your training without gradual progression can stress the body.

- Dehydration in Hot Environments: Exercising in high heat without adequate hydration is a potent combination for increasing blood viscosity.

Preventing Exercise-Related Blood Clots

The good news is that for most people, taking sensible precautions makes exercise a safe and beneficial activity.

Key Prevention Strategies

-

Stay Hydrated: This is paramount.

- Before Exercise: Drink water throughout the day leading up to your workout.

- During Exercise: Sip water or an electrolyte drink regularly, especially during longer or more intense sessions.

- After Exercise: Continue to rehydrate to replace lost fluids.

- Monitor Urine Color: Pale yellow urine is a good indicator of adequate hydration.

-

Gradual Progression:

- Don’t drastically increase the intensity, duration, or frequency of your workouts. Build up gradually over weeks and months.

- Listen to your body. If you feel excessively fatigued or unwell, ease up.

-

Proper Nutrition:

- A balanced diet supports overall health, including circulatory health.

- Ensure adequate electrolyte intake, especially if you sweat a lot.

-

Active Recovery:

- After intense workouts, don’t just sit still. Engage in light activity like walking or stretching to keep blood flowing. This directly counters venous stasis exercise.

-

Listen to Your Body:

- Pay attention to warning signs like persistent leg pain, swelling, or unusual shortness of breath. These could be indicators of a problem.

-

Know Your Personal Risk Factors:

- If you have any of the underlying conditions mentioned earlier, discuss your exercise plans with your doctor. They can provide personalized advice.

-

Compression Garments (for some):

- For endurance athletes, especially those prone to leg fatigue, compression socks or sleeves can sometimes aid circulation. Discuss this with a sports medicine professional.

-

Avoid Overexertion:

- Recognize the difference between challenging yourself and pushing yourself to dangerous extremes, particularly when dehydrated or unwell.

When to Seek Medical Advice

It’s always wise to consult a healthcare professional before starting a new exercise program, especially if you:

- Have a history of blood clots.

- Have a known clotting disorder.

- Have any chronic medical conditions (heart disease, diabetes, cancer, autoimmune disorders).

- Are taking medications that affect blood clotting (e.g., blood thinners).

- Are pregnant or recently gave birth.

- Are undergoing or have recently undergone surgery.

- Experience concerning symptoms during or after exercise.

Your doctor can assess your individual risk profile and help you create a safe and effective exercise plan. They can advise on appropriate hydration strategies and training intensities based on your health status.

Common Misconceptions and Clarifications

Let’s address some common questions and clear up any confusion.

Are All Blood Clots Dangerous?

Not all blood clots are dangerous. The body has a natural clotting mechanism to stop bleeding when injured. However, clots that form inappropriately within blood vessels, especially in veins (DVT) or arteries, can be problematic. If a clot breaks free and travels to vital organs like the lungs (pulmonary embolism) or brain (stroke), it can be life-threatening.

Is “Exercise Induced Thrombosis” Common?

No, exercise induced thrombosis is extremely rare in otherwise healthy individuals. It typically occurs in the context of significant dehydration, extreme overexertion combined with other risk factors, or in individuals with severe, undiagnosed clotting predispositions.

Can Muscle Cramps Lead to Blood Clots?

Muscle cramps themselves do not directly cause blood clots. However, cramps can sometimes be a symptom of dehydration or electrolyte imbalances, which, when severe and combined with other factors, can contribute to a state where blood is more prone to clotting.

What About Blood Clots Exercise in General?

In the vast majority of cases, exercise prevents blood clots. It improves circulation, reduces venous stasis, and contributes to overall cardiovascular health. The cases where exercise might be a contributing factor are usually linked to extreme dehydration, overexertion, and pre-existing risk factors.

Is a Sedentary Lifestyle Worse for Blood Clots?

Yes, a sedentary lifestyle blood clots risk is significantly higher than the risk associated with moderate exercise. Prolonged immobility is a major cause of venous stasis, which is a key factor in DVT formation.

What’s the Danger of a Pulmonary Embolism from Exercise?

A pulmonary embolism exercise risk is not from the exercise itself directly causing the PE. Instead, if a DVT forms (potentially due to extreme dehydration or immobility after intense exercise in a susceptible person), that clot could potentially dislodge and travel to the lungs. This is a severe medical emergency.

Case Studies (Hypothetical Examples)

To illustrate the points, let’s consider a couple of hypothetical scenarios:

Scenario 1: The Marathon Runner

- Individual: A fit, healthy marathon runner.

- Activity: Running a marathon in very hot weather.

- Potential Risk: The runner fails to adequately hydrate before and during the race. They experience significant fluid loss.

- Outcome: Due to severe dehydration, their blood becomes thicker. While they finish the race, they experience calf pain and swelling afterward. This could be due to muscle strain, but in a dehydrated state, it might also signal the early stages of DVT.

- Prevention: If the runner had focused on consistent hydration and listened to their body, the risk would have been significantly lower.

Scenario 2: The Weekend Warrior

- Individual: Someone who works a desk job all week and is generally inactive.

- Activity: Decides to suddenly undertake a very long, strenuous hike without prior conditioning.

- Potential Risk: The intense, unaccustomed physical stress, combined with inadequate fluid intake and prolonged sitting afterward due to exhaustion.

- Outcome: The individual experiences calf pain and swelling after the hike. If they then sit for many hours without moving (e.g., on a long car ride home), this immobility, coupled with potential dehydration from the hike, could increase their DVT risk exercise.

- Prevention: Gradually increasing activity levels and ensuring proper hydration would have made this scenario much safer.

Conclusion: Embrace Movement, Stay Informed

Exercise is a cornerstone of good health and a powerful ally in preventing blood clots. For the vast majority of people, the benefits of regular physical activity far outweigh any minimal risks. The key lies in approaching exercise intelligently:

- Prioritize hydration.

- Listen to your body.

- Progress gradually.

- Be aware of your personal risk factors.

- Consult your doctor if you have any concerns.

By staying informed and taking sensible precautions, you can enjoy the many rewards of exercise while effectively minimizing the risk of blood clots. Embrace movement, stay hydrated, and keep your circulatory system happy and healthy!

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q1: Can very intense exercise cause blood clots?

While rare, extremely intense exercise, especially when combined with dehydration, can thicken the blood and potentially increase the risk of blood clots. This is particularly a concern in endurance events like marathons held in hot conditions without proper fluid management.

Q2: What are the signs of a blood clot after exercise?

Signs of a potential blood clot, such as Deep Vein Thrombosis (DVT), can include persistent pain, swelling, warmth, and redness in a limb, usually the leg. Shortness of breath or chest pain could indicate a pulmonary embolism. If you experience any of these symptoms, seek immediate medical attention.

Q3: Is cycling or running worse for blood clot risk?

Neither cycling nor running inherently poses a greater risk. The risk is primarily associated with the intensity of the exercise, duration, hydration levels, and individual susceptibility to clots, rather than the specific activity itself. Prolonged immobility after any strenuous exercise can be a risk factor.

Q4: Should I worry about blood clots if I have exercise-induced muscle cramps?

Muscle cramps themselves don’t cause blood clots. However, cramps can be linked to dehydration or electrolyte imbalances, which can, in turn, contribute to thicker blood. If you experience frequent or severe cramps along with other risk factors for clots, it’s worth discussing with your doctor.

Q5: How does dehydration during exercise increase blood clot risk?

When you’re dehydrated, your blood volume decreases, and the concentration of blood cells and clotting factors increases. This makes your blood thicker and more sluggish, which can promote blood coagulation and raise the risk of clot formation, a condition known as exercise induced thrombosis in extreme cases.

Q6: What is venous stasis exercise?

Venous stasis exercise is not a standard medical term. However, the concept of venous stasis (blood pooling) is highly relevant. Prolonged immobility, common after intense exercise if one sits or lies down for too long, can lead to blood pooling in the veins, especially in the legs. This sluggish blood flow increases the risk of DVT. Regular movement, particularly leg exercises, helps prevent venous stasis.

Q7: How does a sedentary lifestyle relate to blood clots?

A sedentary lifestyle blood clots risk is significantly higher than for active individuals. Sitting or standing for long periods without moving leads to venous stasis exercise (blood pooling in the legs), which is a primary risk factor for developing Deep Vein Thrombosis (DVT).

Q8: Can exercise help prevent blood clots?

Yes, absolutely. Regular exercise is one of the best ways to prevent blood clots. It improves blood circulation, strengthens the heart, helps maintain healthy blood vessel walls, and reduces the likelihood of venous stasis, all of which are protective factors against clot formation.