What is the timeframe for losing fitness? Generally, noticeable detraining effects can begin within two to four weeks of stopping exercise, with significant declines occurring after one to two months. Can I maintain fitness with minimal exercise? Yes, even a small amount of regular activity can significantly slow down fitness loss. Who is most affected by detraining? While everyone experiences deconditioning time, individuals with higher initial fitness levels or those who train intensely may notice changes more rapidly.

The journey to peak physical condition is often paved with sweat, dedication, and consistent effort. But what happens when life intervenes, and that consistent effort wanes? Many people wonder, “How long does it take to lose fitness?” This is a critical question for anyone who has invested time and energy into their health and wellness. The reality is, fitness isn’t a permanent state; it’s a dynamic one, influenced by what you do (or don’t do). This in-depth look will explore the science behind detraining effects, the timeline for deconditioning time, and what you can expect when you pause your exercise routine.

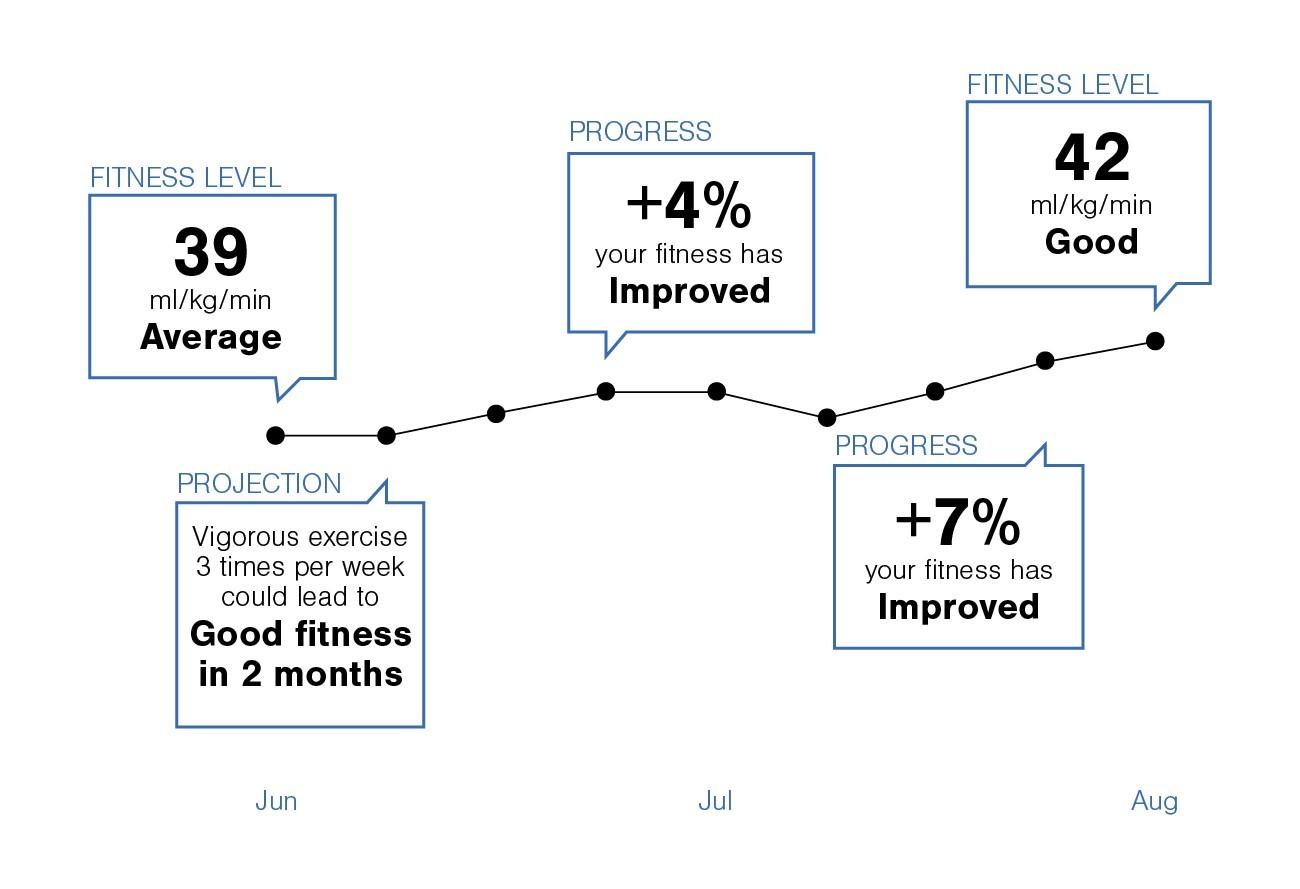

Image Source: www.firstbeat.com

The Science of Detraining: Why Fitness Fades

The human body is remarkably adaptable. When you exercise, your body responds by becoming stronger, faster, and more efficient. Your heart and lungs improve their function, your muscles grow and become more powerful, and your body becomes better at using energy. This process is called adaptation. However, when you stop exercising, your body begins to revert to a less active state. This reversal is known as detraining, and it impacts various aspects of your physical capacity.

The reversibility principle is a fundamental concept in exercise science that states the physiological adaptations gained through training will be lost if training stimulus is removed. This means that the gains you’ve made in cardiovascular health, muscular strength, endurance, and flexibility are not permanent and require ongoing maintenance.

Muscle Loss After Stopping Exercise: The Shrinking of Strength

One of the most noticeable aspects of stopping exercise is muscle loss after stopping exercise. When you lift weights or engage in resistance training, your muscle fibers experience microscopic tears. Your body repairs these tears, making the muscles stronger and larger (hypertrophy). Without the stimulus of resistance training, your body no longer needs these larger, stronger muscles, and they begin to shrink.

- Initial Changes (1-2 Weeks): In the first couple of weeks without resistance training, you might not see significant muscle loss, but your muscles will feel less “pumped” and may have reduced endurance. The neurological adaptations that made your movements efficient start to fade.

- Noticeable Strength Decline (2-4 Weeks): After about two to four weeks, you’ll likely start to notice a decline in your strength. You might struggle with weights you previously handled with ease. This is due to a combination of reduced muscle mass and decreased neuromuscular efficiency.

- Significant Muscle Loss (1-2 Months): Over one to two months of inactivity, you can expect a more substantial decrease in muscle mass and strength. Studies suggest that a significant portion of strength gains can be lost within this timeframe.

- Long-Term Effects (Months to Years): If inactivity continues for many months or years, muscle mass can revert close to pre-training levels, though some residual adaptations may remain for longer, especially in individuals who trained for extended periods.

It’s important to note that the rate of strength loss timeline can vary based on the type of exercise, intensity, and individual factors. Endurance training also affects muscles, leading to a decrease in the oxidative capacity of muscle fibers.

Cardio Decline: The Slowing of the Engine

Your cardiovascular system, including your heart and lungs, is incredibly responsive to exercise. Aerobic training increases your heart’s stroke volume (the amount of blood pumped per beat), improves your lung capacity, and enhances your body’s ability to use oxygen. When you stop cardio, these improvements begin to reverse.

- Aerobic Capacity Reduction (2-4 Weeks): Your aerobic capacity reduction, often measured by VO2 max (the maximum amount of oxygen your body can use during intense exercise), is highly sensitive to changes in training. Within two to four weeks of stopping aerobic exercise, VO2 max can decrease by 5-15%. This means you’ll likely get winded more easily during everyday activities or workouts.

- Endurance and Stamina Fades (2-4 Weeks): The sustained energy production systems that support endurance activities also decline. You’ll find your stamina diminishing, and activities that once felt comfortable will become more challenging.

- Heart Rate and Blood Pressure Changes (4-8 Weeks): Over a longer period, resting heart rate may increase, and blood pressure could trend upwards as your cardiovascular system becomes less efficient.

- Capillary Density and Mitochondrial Function: With consistent training, your muscles develop more capillaries (tiny blood vessels) and mitochondria (the powerhouses of your cells). These adaptations improve oxygen delivery and energy production. When you stop training, these also decrease, contributing to the cardio decline.

The speed of this cardio decline depends on the intensity and duration of your previous training. Someone who ran marathons will likely experience a slower decline than someone who jogged for 30 minutes twice a week.

Factors Influencing the Detraining Period

While general timelines exist, the detraining period is not a one-size-fits-all phenomenon. Several factors influence how quickly and how much fitness you lose:

1. Initial Fitness Level

- Higher Initial Fitness: Individuals who start with a higher level of fitness often have greater physiological reserves and more robust adaptations. While they will still experience detraining, the rate of decline might be slightly slower, and they may retain a higher baseline level of fitness for longer compared to someone with a lower starting point. For example, a highly trained athlete might still perform better than an untrained individual after a period of inactivity, even if they have lost significant fitness.

2. Type and Intensity of Previous Training

- High-Intensity Interval Training (HIIT): While HIIT is excellent for building fitness quickly, the benefits can also diminish relatively fast if not maintained.

- Endurance Training: Long-distance runners or cyclists build significant aerobic capacity. While they may retain some of this capacity longer due to the sheer volume of training, significant declines in VO2 max and lactate threshold can still occur within weeks.

- Strength Training: As discussed, muscle mass and strength gains are susceptible to detraining. The intensity and volume of your previous strength training will influence how much you lose and how quickly.

- Cross-Training: Engaging in a variety of activities can help maintain a broader fitness base. However, even with cross-training, cessation of all activity will lead to detraining across all components.

3. Duration of Training

- Longer Training History: If you have been consistently training for many years, your body may have more ingrained adaptations. This can mean that while you will still experience exercise cessation impact, you might regain your previous fitness levels faster when you restart compared to someone who trained for a shorter period. There’s a certain “memory” in the muscle and cardiovascular system.

4. Age

- Slightly Slower Recovery: While older adults can and should exercise, their bodies may adapt a bit more slowly than younger individuals. This can also mean that detraining might manifest slightly differently, although the general principles remain the same. However, older adults may also find it harder to regain lost fitness if they become inactive for extended periods.

5. Genetics

- Individual Variation: Genetics plays a role in how our bodies respond to training and how quickly we lose fitness. Some individuals may be genetically predisposed to build and retain muscle or cardiovascular efficiency more readily than others.

Quantifying Fitness Loss: A Closer Look

Let’s break down the strength loss timeline and cardio decline with more specific examples from research.

Strength Loss Timeline

| Time Without Training | Expected Strength Loss | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 2-4 Weeks | 5-10% | Initial loss due to neurological factors and reduced muscle activation. |

| 1-2 Months | 10-25% | More significant loss due to muscle atrophy and reduced protein synthesis. |

| 3-6 Months | 25-40% | Substantial loss, potentially reverting to near untrained levels. |

| 6+ Months | Varies | Can continue to decline or plateau at a lower level. |

Note: These are estimates and can vary significantly based on individual factors.

Cardio Decline (VO2 Max)

| Time Without Training | Expected VO2 Max Decline | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 2-4 Weeks | 5-15% | Noticeable reduction in aerobic capacity and endurance. |

| 1-2 Months | 15-30% | Significant decline, impacting performance in aerobic activities. |

| 3-6 Months | 30-50% | VO2 max can approach pre-training levels. |

| 6+ Months | Varies | Continued decline or plateau at significantly lower aerobic capacity. |

Note: These are estimates and can vary significantly based on individual factors.

Other Components of Fitness

- Flexibility: Flexibility can also decline, though typically at a slower rate than strength or aerobic capacity. Within a few weeks of inactivity, you might notice stiffness and a reduced range of motion.

- Body Composition: While stopping exercise, if your caloric intake remains the same or increases, you are likely to gain body fat. This is because your metabolic rate may decrease slightly with reduced muscle mass and activity levels.

The Myth of “Losing All Gains”

It’s important to dispel the myth that stopping exercise means you lose all your hard-earned gains. The reversibility principle does not imply a complete erasure of past adaptations.

- Muscle Memory: While not a true biological “memory” in the way we think of cognitive memory, your muscles and nervous system retain some adaptations. When you restart exercise, you often experience “muscle memory” which allows you to regain lost strength and muscle mass much faster than it took to build it the first time. This is partly due to the increased number of myonuclei (the control centers of muscle cells) that persist even after muscle atrophy.

- Cardiovascular Health: Similarly, while VO2 max decreases, the structural and functional improvements in your heart and blood vessels may not entirely disappear.

Fitness Maintenance: The Key to Longevity

The concept of fitness maintenance is crucial for long-term health and well-being. It highlights that consistent, albeit potentially less intense, activity is key to preserving the benefits of your training.

How Little is Enough?

Even a reduced exercise regimen can significantly slow down detraining.

- Maintaining Strength: Aim for 1-2 resistance training sessions per week, focusing on compound movements. This is often enough to largely preserve muscle mass and strength.

- Maintaining Cardio: 2-3 sessions of moderate-intensity aerobic exercise per week can help maintain a good level of cardiovascular fitness. Even shorter durations (20-30 minutes) can make a significant difference.

- Active Lifestyle: Beyond formal exercise, simply being more active throughout the day – taking stairs, walking more, standing at work – contributes to overall fitness and can help mitigate detraining.

Restarting After a Break

If you’ve had to stop exercising, don’t despair! The key is to ease back into it gradually.

- Start Slowly: Begin with lower intensity and shorter durations than you were accustomed to.

- Listen to Your Body: Pay attention to any aches or pains. Overtraining too soon can lead to injury.

- Focus on Consistency: Aim for regularity rather than pushing for peak performance immediately.

- Be Patient: It will take time to regain your previous fitness levels, but with consistent effort, you can get there.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q1: If I stop exercising for a week, will I lose all my fitness?

A1: No, a single week of inactivity will have minimal impact on your overall fitness. You might feel a little less energetic, but significant detraining takes longer.

Q2: Is it harder to lose fitness if I have been training for a long time?

A2: Generally, yes. Longer training histories often lead to more robust adaptations, meaning you might retain some benefits for longer and regain fitness faster when you restart.

Q3: Does body composition change quickly when I stop exercising?

A3: Body composition can start to change within a few weeks, especially if your diet remains the same or you increase your caloric intake. Without the calorie expenditure from exercise, fat gain is more likely, and muscle mass may decrease.

Q4: Can I maintain fitness with just 30 minutes of exercise per week?

A4: While 30 minutes a week is better than nothing, it’s generally not enough to maintain peak fitness levels. However, it can significantly slow down detraining compared to complete inactivity. For maintenance, aiming for at least 2-3 sessions per week of moderate activity is recommended.

Q5: If I stop strength training, will my muscles turn into fat?

A5: No, muscle and fat are different tissues. Muscle does not convert into fat. When you stop strength training, your muscles may atrophy (shrink), and if you continue to consume excess calories, your body may store more fat, leading to an increase in body fat percentage.

In conclusion, while fitness can indeed fade when you stop exercising, the exact timeframe is influenced by many factors. By understanding the science behind detraining effects and the exercise cessation impact, you can make informed decisions about fitness maintenance and approach breaks from training with a clear perspective, knowing that your hard-earned progress is not lost forever.